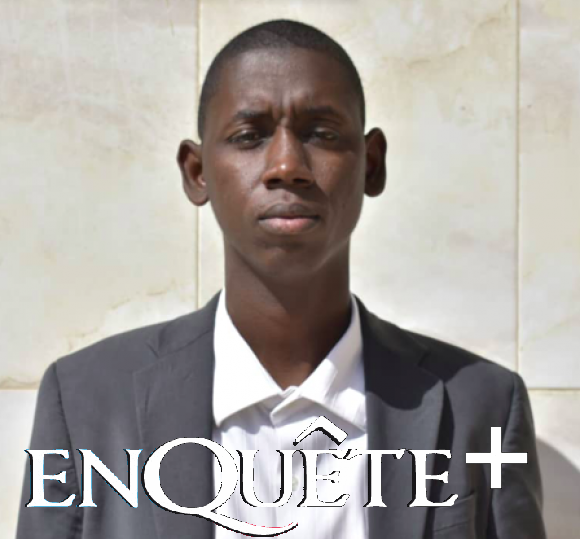

Mamadou Mballo, Program Officer for Land Governance at the Pan-African Institute for Citizenship, Consumers and Development (Cicodev Africa), dissects the many shortcomings at the root of land disputes in Senegal. For the doctoral student in public law at the Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, if land conflicts are to be reduced, land governance must be reinvented at the local level.

There are a lot of land conflicts in Senegal at the moment. What explains this?

The resurgence of land conflicts in Senegal leaves no one indifferent. Lately, not a day goes by without the media echoing it. Such a situation worries the local farmers actors, disrupts social peace and raises questions to the legal experts as to the root causes of such a phenomenon. Three fundamental reasons are likely to explain the recurrence of land conflicts in different parts of the country.

First of all, there are certain legislative inadequacies. By adopting Law 64-46 of June 17, 1964 on the National Domain Code, the Senegalese legislator put an end to the customary rights of farmers over their land. It thus called on land users at the time to register their land. However, farmers did not heed this call and continued to manage their land holdings according to their beliefs. The Law of 64 thus promoted the coexistence of two regimes (customary and national domain), which is the source of many of the land conflicts noted to date.

Secondly, this same law on the national domain, through its implementing decree, stipulates that in order to be assigned land in the national domain, one must belong to the community on the one hand, and have the capacity to develop it on the other. However, the prefectoral decree that was supposed to specify the conditions for development was never issued. This situation has resulted in several areas of land being assigned to private individuals and fenced off without any development, thereby preventing the farmers from using them. This fuels a sense of injustice among the traditional owners, who sometimes do not hesitate to want to take back the land.

In addition, there is a kind of ” foul play ” by local authorities, who take advantage of their authority to allocate large tracts of agricultural land to private investors without consulting the local population. These mostly hidden allocations are at the root of conflicts between communities, elected officials and investors.

If we want to reduce land conflicts, we need to reinvent land governance at the local level. Because local authorities have too many powers in land tenure matters that most of them use against the interests of local communities.

Finally, it must be noted that the absence of land management/planning tools (land use and land use plan, cadastre, etc.) is not also conducive to good land governance at the local level. Local authorities are experiencing real difficulties in controlling their land base. The current land conflict in Ndingler is a stark reminder of the risks of conflict that are inherent in inter-communality.

In your opinion, is there a real political will to solve the land tenure problem in Senegal?

The various attempts to reform the land sector are sufficient proof of Senegalese decision-makers’ political will to solve land tenure problems. Since 1996, with the ”famous” land tenure action plan to the national land tenure policy document in 2017 through the law of agro-sylvo-pastoral orientation of 2004. Unfortunately, all of these efforts have failed because of a lack of capacity to negotiate a consensus on its objectives. The political will of the State to take control of rural land and to allocate it, as a priority, to agribusiness has always clashed with farmers’ civil society organizations, which, each time, have succeeded in blocking projects that they considered unacceptable.

If there has been political will, it should be relativized, given the recent actions of the Senegalese authorities. Indeed, the “brutal” dissolution of the National Commission for Land Reform, just after the land policy document was issued, sounds like a failure in the land reform process. The various outbursts of the President of the Republic on this document are not reassuring as to the continuation of the reform.

At the same time, the government continues to take regulatory measures on land tenure (law on special economic zones). Similarly, since last year, new land programs have been launched with the support of partners such as the World Bank and German International Cooperation. The State seems to be more in a dynamic of sectoral reform than in a rationale of finding a strong consensus on the management of the national land heritage. This gives rise to fears that we are still far from resolving land tenure problems/conflicts.

Do you have any statistics on land conflicts at CICODEV?

Absolutely, CICODEV has been working on land grabbing issues for a long time. It must be said that this is a somewhat old phenomenon. In 2010, CICODEV conducted a study on the extent of the phenomenon in Senegal. The results of the study had concluded that in the space of 10 years (from 2000 to 2010), 650 000 hectares of land have been granted to 17 foreign or national private investors in this country. This represents 16% of Senegal’s arable land. Such a situation has a very negative impact on the daily life of local communities, particularly in terms of food and nutritional security, local employment of youth and women, energy security and the sustainability of natural resources.

There is a lot of talk about land grabbing or land spoliation. Is all this land grabbing illegal?

While most land grabbing is illegal, not all land grabbing is against the law. On the one hand, the law does not define a range in terms of surface area for land allocations to individuals, investors or not, but it also provides the State with the possibility to allocate land to individuals. Indeed, article 3 of the NDA recognizes the possibility for the State to register lands in the national domain. In such a case, the registered lands are in principle in the private domain of the State. From that moment on, the law authorizes the State to make the land in question available to any individual, including investors who request it.

From the moment the State can request the registration of land in the national domain, it is easy for the State to allocate it to investors or any other person for private use, sometimes even to the detriment of the interests of communities. This provision can take the form of a lease or a sale after legislative authorization. While this may be unfair, from a legal point of view, if it can be called a monopoly, it is legal.

The National Domain Act (NDA) has been in existence for a long time, but its application is problematic in many cases. Is this law still relevant?

The 1964 National Domain Act has two main objectives: the socialization of land ownership and the economic development of the country (exclusion of individual ownership, being a member of the community and capacity for development). However, this law has not been followed up in that it required farmers and other users to register their rights six months after the adoption of the implementing decree. By removing customary rights and establishing a modern law, this law would naturally be met with resistance from the communities who continue to assert their customary rights on these lands.

From this point of view, one can indeed speak of gaps between social realities and the law on the national domain.

However, upon closer examination, the law on the national domain is more ineffective than inadequate. Everybody knows that this law prohibits any form of transaction on the lands of the national domain; that this domain is not private property. However, everyday reality shows that the principles of the law are being misused and people, political elites and other actors, are selling the lands of the National Domain without being worried.

Rather than questioning existing rights to community land, land reforms would benefit from recognizing and strengthening these rights. We need to adapt our laws to our societies, not adapt our societies to our laws.

Does the legal and regulatory framework of land governance in Senegal make it possible to secure land tenure?

In view of the inadequacies of the law on the national domain, which governs most of the land subject to land conflicts, Senegal would benefit from reforming its legal arsenal relating to land management. Senegalese decision-makers, as well as other stakeholders such as civil society, have understood this for a long time. However, reform is clearly not an easy thing to do, especially for a sector as strategic as land tenure. Although we must keep in mind that a society cannot be changed by decree, as Mr. Crozier rightly pointed out. This is to say that there is no guarantee that with the adoption of a future law on land, we will manage to solve all the problems in this sector.

In any case, reform is necessary. This reform will have to be based on certain fundamentals that put people at the center of land governance. In this regard, a few suggestions can be put on the table: Recognize the legitimate land rights of farmers; recognize and regulate land mobility (inheritance, transferability, leasing under certain conditions, access to credit for farmers without the possibility for banks to seize land); strengthen transparency in land allocation at the local level (expansion of state commissions, qualified majority deliberation, institutionalization of citizen control through joint village committees) and prioritize the achievement of food sovereignty in the use of land in Senegal.