| In Senegal, land resources are increasingly the object of conflicts that have become increasingly violent, with risks that can compromise peace and the social climate. This instability is largely due to the confusion surrounding land legislation, which is ignored by communities, and to social practices that are not recognized by the law. This does not exclude the emergence of dubious practices intended or maintained by the land administrators. In this article produced by Sud Quotidien, in collaboration with Osiwa, the actors recommend finalizing the land reform and above all, implementing the recommendations of the National Commission on Land Reform (CNRF). |

| Throughout the country, land management is being questioned. This is due to the large number of actors involved in land management, which suggests a certain lack of coordination and harmonization between the various actors. But one thing is certain: each actor has specific areas of expertise. For example, there are “local authorities, headed by municipal councils, which manage land in the national domain, particularly land located in rural areas and intended primarily for agriculture and rural housing. The Water and Forestry Services, which manage part of the land in the national domain. These are classified forests or classified areas,” said the Executive Director of the Pan African Institute for Citizenship, Consumers and Development (CICODEV ) Amadou Kanouté.

According to him, “there is a state domain composed of a public domain and a private domain whose management is ensured by the Ministry of Finance and Budget, in particular by the Directorate of Domains. These are the services of the Ministry that issue all leases, authorizations to occupy and land titles. Other services such as “urban planning, land development, Apix or Sapco in charge of the development of tourist areas also have a say in the land chapter with each of the specific texts that frame their competences”, he adds. In the same breath, the Executive Director of the Agricultural and Rural Prospects Initiative (Ipar) emphasized that the State domain is divided into two regimes, namely “public and private domains”. For the private domain, he said, “it is composed of movable and immovable goods and rights acquired by the State, free of charge or for a fee”, according to the modes of common law “buildings acquired by the State through expropriation; buildings registered in the name of the State; buildings pre-empted by the State; movable and immovable goods and rights whose confiscation is pronounced for the benefit of the State; and abandoned buildings whose incorporation into the domain is pronounced in accordance with the provisions of article 82 of the decree of July 26, 1932 on the restructuring of the Land Ownership System”, he explains. The State called upon to play its part in reducing land conflicts As a general rule, there is only one land governance model, according to Mr. Kanouté. According to him, “it is the one provided by the legal and regulatory framework in force in the land sector that all the actors and local authorities who have management competence in land matters must respect”. However, he makes a point of specifying that “there is no such thing as “sight-seeing” in this area”. Today, he continues: “Because of the specificity of certain zones and the support in many cases of actors and civil society organizations, it may happen that local authorities decide to set up land management tools to reduce conflicts and confrontations/competitions over land. To convince himself of this, he cites as an example of land charters that are well known to local actors. On this, he said: “These charters have a lot of merit because they are generally quite inclusive and reflect the needs of local actors. The State, which is familiar with these mechanisms, would benefit from capitalizing on them and drawing inspiration from them as much as possible to reduce the many land conflicts in rural areas. Ipar considers that the procedures for making land available are different depending on the status of the land, i.e., the national domain, the State domain and the domain of private individuals. As for the national domain, “the procedures also change according to the zones which are the urban zone, classified, pioneer and the terroir zone, the latter being reserved for rural housing, agriculture and livestock,” says Executive Director Cheikh Oumar Ba. For the latter zone, he explains, “management is decentralized to the communes and the deliberations are submitted for approval to the representative of the State, who may be the sub-prefect or the prefect for any area between 0 and 10 hectares, the prefect exclusively for areas between 10 and 50 hectares, and the regional governor for any area greater than 50 hectares, with registration at the secretariat of the government. At the commune level, he continues, “the deliberation involves the municipal council, which deliberates, the land commission, which is the technical arm, the village chief, who is a member of the said commission when it visits a piece of land in his village, and the mayor, who signs the deliberation. The procedure goes from the request to the installation on the land. This deliberation is limited to the right of use, implying a ban on all forms of land transactions, an absence of automatic devolution of property, and an absence of the power to use land in the national domain to guarantee a loan. The implementation order of the State domain code is requested According to the former director of domains and expert of Ipar, Alle Sine: “It is law No. 76-66 of July 2, 1976 on the Domain Code which establishes in its Article 9 the principle that the public domain is inalienable and imprescriptible”, he emphasizes. This means that it is forbidden to sell a portion of the public domain, and that one cannot own it by invoking a long-term occupation (acquisitive prescription). However, “this rule is mitigated by the legal possibility of removing a property from the public domain, to incorporate it into the private domain and, thus, to strip it of the protection initially conferred by the mantle of public domain”, he insists on specifying. This possibility is created by a so-called declassification act. Thus, a plot of land in the public domain, once declassified, “is now in the private domain and is subject to the same rules of management, and occupation by way of long lease, or final transfer that may lead to the delivery of the land. The holding of a real right thus cancels the precautionary and reversible character of the occupation and confers the right to build on the land”. In this respect, he says: “It must be admitted that there is a legal vacuum with regard to the declassification procedure. This results from the fact that until today, contrary to the private domain of the State which had its decree of application (law 81_557 of May 21, 1981), there is still no implementation decree for the State domain code as far as the public domain is concerned “. Since then, one can validly ask oneself how to proceed to declassify a piece of land belonging to the public domain. It is understood that in any case, whatever the procedure implemented, it will have to lead to the signature of a presidential decree to consecrate this entry into the private domain. “This legal vacuum may therefore constitute an open door to various interpretations and practices that may later lead to disputes such as those recorded today on the Dakar coastline,” he said. Mr. Kanouté of the Pan-African Institute for Citizenship, Consumers and Development cleared up the confusion by indicating that “there is no distinction to be made according to zones but rather according to the nature and legal regime of the land. This will make him say that “if the land for which the title is requested is in the national domain, it is the Territorial Collectivity that will be competent and the act of assigning the parcel will be a deliberation”. On the other hand, if the land comes under the State domain, both public and private, from that moment on, it is “the Directorate of Domains that will be competent to give the applicant either an authorization to occupy, or a lease, or to establish a land title for him”, he says.

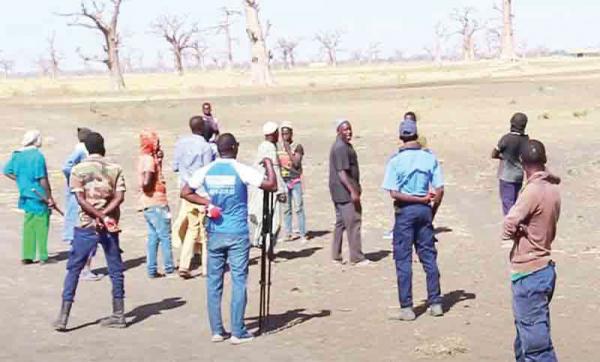

Compliance with land allocation and deallocation procedures at the local level requested. In order to calm the social climate, a number of actions need to be taken, in particular “to ensure that responsible land investments are made that involve all stakeholders and that they give their free, preliminary and informed consent,” according to Mr. Ba of Ipar. In this regard, “building the capacities of actors to ensure that all actors are aware of the normative land framework. Otherwise, the land reform process must be finalized by implementing renewed land governance based on the search for convergence between practices and legislation,” he says. Otherwise, he believes, “the current situation will persist, characterized by confusion between, the land legislation on one hand, which the communities ignore, and on the other hand, social practices that are not recognized by the law, and between the two, the emergence of practices that increase the desired or maintained confusion. Mr. Kanouté highlights a certain number of key principles for land pacification. According to him, these include the principle of “citizen participation, informing the population in a clear and exhaustive manner before any project with a strong land impact, involving the communities upstream, ensuring that they are not dispossessed of their land definitively, instituting citizen control mechanisms on the land in each territory, including the State and the local authorities, and finally, ensuring that the law is respected in the procedures for allocating and withdrawing land at the local level. Clearly, the State would benefit from better equipping the territorial communities in terms of tools for managing their land base, so that ” dual deliberations are avoided and the issue of territorial overlapping linked to intercommunality is reduced “.

The transformation of consensus into legislative and regulatory acts desired

It is encouraging that for the first time in Senegal, discussions on the land issue have led to the development of a national land policy document that reflects the consensus on land issues, as part of an inclusive and participatory process. The National Land Reform Commission is considered to be an interesting process in terms of the new approach to implementing land reforms in accordance with the orientations contained in the African Union’s Framework Document and Guidelines on Land Policies in Africa, and has made it possible to take a first step towards transforming the consensus into legislative and regulatory acts. However, it must come to an end. “The President of the Republic dissolved the commission after the submission of the document and since then the process has come to a halt,” he regretted. Currently, “all actors are organizing to remind the President of the Republic of the urgency to complete the reform, especially since land tensions are widespread throughout the country and the President of the Republic has admitted that a large percentage of alerts he receives concerns the land issue,” he said.

When asked about the follow-up to the report of the national land reform commission, Mr. Kanouté said: “We have no news, at least officially, about the follow-up to the national land policy document of 2017. During the few times that this document was discussed, the Head of State did not seem to be very enthusiastic about the conclusions that were reported to him and that would have resulted from the work of the Commission.

Today, “the State is more in a logic of reform through tools as evidenced by the projects and programs underway in the land sector (Procasef, Promogef etc.),” he notes. As a civil society, this situation is very worrying for us because “it does not promote dialogue, consultation between the different families of actors, which is very unfortunate. This is another opportunity for us, while welcoming the decision of the Head of State to prohibit the granting of land titles on agricultural land in rural areas, to ask him to update the land tenure in its entirety and follow up on the conclusions and recommendations of the now defunct National Commission on Land Reform. JEAN PIERRE MALOU May 17, 2021 |

Actors involved in implementing the Cnrf’s recommendations